Long Live Paradise

- Elizabeth Knight

- Apr 23, 2021

- 12 min read

It’s July 10, 1946, a hot, sunny Wednesday in Detroit. The breeze carries the scent of water and the sounds of laughing children from beaches on the banks of the Detroit River, whose glittering surface frames Windsor’s low skyline in blue sequins. About a mile and a half away, the Paradise Theatre stands on the corner of Woodward Avenue and Parsons Street with the words “COUNT BASIE AND HIS ORCHESTRA” spelled out in block letters on the theatre’s large marquee. In the windows, posters displaying fat, curling black letters, “Count Basie and his orchestra! In person,” hang, perhaps displaying a photograph of Count Basie himself, with a grin under his english mustache, and his hands resting on the keys of a grand piano. These posters show today’s date, with a time listed for a matinee, and one for the evening. A line forms at the box office window, excitement bubbling up into the air. Perhaps, if you were there, you and your friends would be chattering excitedly, dancing in place, oh to see such a talented artist right here in your hometown!

Finally the doors would open, and you would walk through the round lobby, over worn red carpet, under a sparkling chandelier. You would take a left and climb the stairs to the balcony before entering the golden hall. Round corona-like lights hover like halos over your head, and your eyes follow the steep rows of seats, trimmed with little lights glowing by your feet, to the stage below. The walls are decorated with intricate plaster sculptures, angels and lyres, and the ceiling is painted with red and white vines. Red curtains frame the wooden stage, and right in the middle sit a few rows of chairs on risers, a stand-up bass lies on its side beside a shiny drum set, and then the piano, just like the one on the poster, is off to the left.

The audience would hush as the lights lowered and the last of the guests took their seats, and as Basie and his musicians walked onto the stage, everyone would erupt into shouts and whoops of joy, clapping and clapping until he’s able to quiet them down. He would introduce his band in a low, rumbling voice, and then would come the humming saxophones, screaming trumpets, squealing clarinets, trombones would blast out low glissandi, and the rhythm section would create a beat which didn’t allow still feet from the concertgoers. They say it was like a party on a Saturday night. Sometimes there were more people than seats, and the balcony would shake under the weight and movement. By the time the show was over, the audience was often so riled up that they didn’t want to go home, but they did with gleaming smiles on their faces, undoubtedly.

~

The Paradise isn’t the only theatre to have existed on that same corner of Parsons Street and Woodward Avenue. It isn’t even the only theatre to have existed in the same building. In fact, I would be much more accurate in telling you that it is the very same theatre existing under several different names, each one entailing an entirely different kind of performance. Most notably, it seems, is the name Orchestra Hall, the name under which the hall currently exists, and under which it is known as the home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1887, but it was a disorganized, unpolished ensemble. For some time, the amount of money the organization was making wasn’t even breaking even with the costs, despite the musicians being grossly underpaid. The orchestra disbanded in 1910, and the rebirth of the DSO didn’t come until four years later. It was another four years before the orchestra finally began to thrive under conductor Ossip Gabrilowich, a Russian pianist who was in town to perform as a soloist with the DSO, and who just happened to serve as an excellent replacement, one day, for a no-show conductor. After resounding approval from the audience, he stuck around. Gabrilowich brought a lot to the DSO, including his incredible talent and grounded, inspiring personality, but one of the most important things that he brought to the orchestra was a home.

When offered the position of head conductor, Gabrilowich said, “I’ll come. If you build a concert hall worthy of my artistry, this orchestra, and Detroit.” He demanded that the hall be finished before the start of the next season, and surprisingly enough, the board complied. He was bringing in money, and because of him, the DSO was better than they had ever been before.

More surprising than the compliance of the board was the subsequent speed of construction. A substantial task: building a 2,000 seat hall, complete with intricate decoration and all of the capabilities necessary to hang lighting and theatre sets, was finished in six months. Rumor has it that construction workers were still finishing up as guests walked in the front doors of Orchestra Hall on it’s opening night, October 23, 1919. The hall was immediately embraced by the concertgoers for it’s incredible acoustics, which was largely coincidence, and was eventually it’s saving grace.

In an article published by the Detroit News on October 24, 1919, the day after the opening, the hall’s reception was described with resounding praise. “Let us say that the auditorium, in point of appearance as well as in point of accomodations, exceeded all sanguine expectations… As for the hall there’s one innovation for which the concertgoer will find words weak to express all of his gratitude- the yellow toned lights which give perfectly adequate illumination in the auditorium and yet are quite restful to the eye. The acoustics are reported good in almost all sections of the house.” A proud evening for the orchestra and for Detroit, “to which every factor contributed further joy,” included a performance of “The Star Spangled Banner” and Beethoven’s fifth symphony.

~

The DSO thrived for years, but by 1939, Gabrilowich was long gone, and things were not looking good for the orchestra. The Great Depression had taken its toll on the DSO’s funds through the 1930s. People couldn’t afford to spend money on tickets, and it didn’t seem like they wanted to either. In 1936, Franco Ghione, a new conductor who didn’t speak much English and apparently had a nasty temper, had taken over. He left the musicians uninspired, and being primarily an operatic conductor, his knowledge of symphonic repertoire was limited, causing his programs to be less than extraordinary. When they could no longer afford to stay in Orchestra Hall, the DSO was forced to go elsewhere, and the hall was left abandoned.

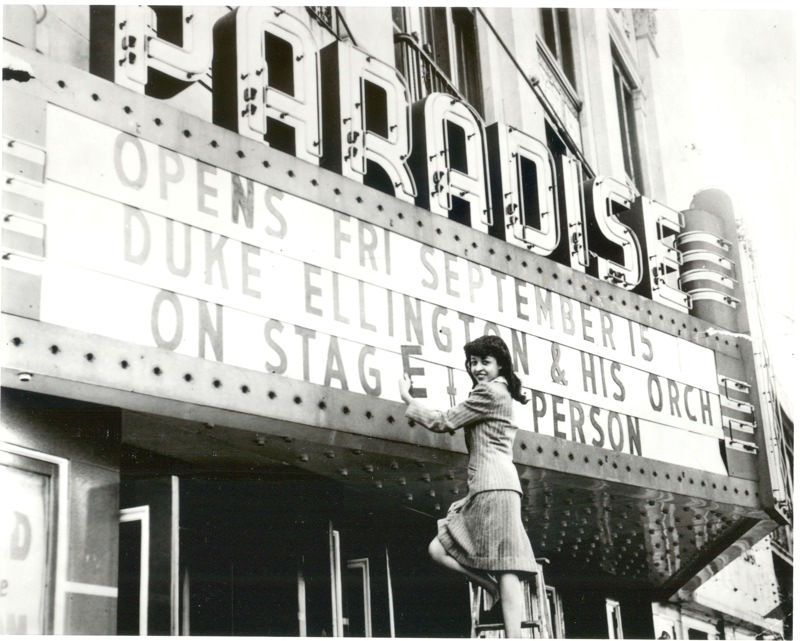

It served as a movie theatre and burlesque house called the Town Theatre until 1941, when two Jewish entrepreneurs bought the building. Local historians say that a group of black businessmen originally tried to buy the building, but when they were turned down because of their race, they turned to the Jewish entrepreneurs for help. The hall was then renamed Paradise Theatre after the Paradise Valley neighborhood, the leading black business district in Detroit. Louis Armstrong opened the theatre on Christmas Eve, and it was immediately, unsurprisingly, a huge hit. “We saw many stars,” John McDonald, a former resident of the Black Bottom, said in an interview in 1985, “The acoustics were very super, some of the best that there is in the country.”

The Paradise Theatre quickly became a place where all of the most famous black jazz musicians went while they were on tour, including Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington. It gave black people of all ages the opportunity to experience music from all over the country. “It was different from local jazz clubs and bars because the Paradise was a big name place where young people were allowed to go,” Mark Stryker, author of Jazz From Detroit, said, “You couldn’t get into those places if you weren’t 21. It was a place where so many young jazz musicians heard their idols and got inspiration.” Having a place like the Paradise Theatre available kept all black Detroiters in touch with their culture, and allowed them a way to communicate with other people who shared that culture.

The theatre lived on for ten years, and substantially contributed to musical traditions in Detroit. Due to competition from other venues, as well as a change-up in the style of popular music, however, the theatre was forced to close in 1951, giving way to venues hosting bebop and R&B.

~

However long ago it was, I can remember quite vividly the first time I played in Orchestra Hall. I walked onto the stage, and immediately was struck by the warmth of the lights on top of my head, and the warmth of the colors, but most of all the warmth of such common sounds as flipping pages and stands scraping across the wood floor. I used to play in the Detroit Symphony Youth Orchestra, and I thought I must have been playing in the best youth ensemble in the world. It took me a few rehearsals to figure out that wasn’t quite the case. Another ensemble needed to use the hall, so we moved to a generic rehearsal hall in the Detroit School of Arts next door, and that’s when I realized, however good we might have been, that hall was like magic. It could make a chainsaw sound lucious and affable. Robert Williams, principal bassoonist of the DSO, said of the hall, “When you play in it, you can feel how good your sound is. It’s always been a great hall. A lot of orchestras would kill for a hall like this.”

The reason for the hall’s near-perfect acoustics is a combination of things which all probably happened because of the time crunch during construction. The small size and the plain, hard plaster walls allow incredible resonance and clarity, and the fly tower and trap space, which were added in just in case the hall was to ever be used for opera or theatre provide great bass response. This creates the warm, pleasant quality that Orchestra Hall is famous for, and which made it worth saving from its imminent demise.

In 1970, Paul Ganson, former assistant principal bassoonist of the DSO, took a group of people and walked through a decimated Orchestra Hall. They had to use flashlights because the only light available was that which filtered in through gaps in the ceiling. Perilous glooms were cast in all of the corners, live birds fluttered around, chunks of ceiling came crashing to the ground now and then, and there was water dripping through the holes that those missing chunks created. There was no better way for him to describe it than a “sad, soggy, sorry mess.” Despite its appearance, however, he had heard recordings, and he knew it was worth saving. A member of his little group took out his violin and stood in one of the box seats to play a Bach Partita, and sure enough, it sounded beautiful. The only problem was that not long after this visit, the building had been sold to Gino’s Burgers, a fast food chain, and was being prepped for demolition.

Upon receiving this news, Ganson jumped into action and launched the Save Orchestra Hall campaign. They were able to raise enough money to buy the building back in 1972, and by 1987, the orchestra was able to return to its home. The amount of support that this movement received goes to show how much this building has meant to people. There were posters with an image of Orchestra Hall broken in half pasted up on street lamps, bus stations and restaurants, but they didn’t all say the same thing. Mark Stryker said that one of the most important things he discovered while researching was that, “in the 70s and 80s- decades after Paradise Theatre wasn’t there anymore, black people were still calling it Paradise Theatre. They didn’t say save Orchestra Hall. They said save Paradise Theatre.”

~

I walked into the Detroit Historical Museum one afternoon, and wandered around the very first room in the museum; this round, sunny space encircled by a timeline. As I read about all of the major events in Detroit’s history, I couldn’t help but notice the lack of any mention of music other than a few brief lines about Motown and Jack White. I was relieved, when I finished my trip around the room, to find myself standing in front of a set of doors that lead to a room dedicated to music in Detroit, but upon entering, I quickly realized I wouldn’t find what I was looking for there either. On the Detroit Historical Society webpage, it’s described as a place where people can “learn about Detroit's rich musical legacy by reading about the international stars who have called our city home. From Aretha Franklin to Madonna to Bob Seger to Alice Cooper, Detroiters have made an impact in every genre of music,” but it seems as though Motown is considered the starting point. The Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods, where almost every Detroit based jazz club and bar existed, aren’t mentioned.

It’s almost as if all of the beginnings of music in Detroit have been erased from common knowledge, and that seems strange. When most people hear the words “music” and “Detroit” in sequence, the first thing they think of is Motown, but nobody ever wonders where it came from. Historically, all music has developed in a very similar way. Ideas are passed down from one era to the next, and they inspire those who create new music. Motown is made up of a lot of genres, including jazz, soul, and R&B. It was merely added on to the ever developing roll of Detroit’s musical timeline. The musicians who thrived in the 60s and 70s had to get their inspiration from somewhere, and for many, that inspiration came both directly and indirectly from Paradise Theatre. Curtis Fuller, a well known American jazz trombonist who was in Count Basie’s orchestra from 1975-77, first heard JJ Johnson play with Jacquet Illinois at Paradise Theatre, and that was the very performance that prompted him to pursue music. Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records, grew up in Detroit, and his teenage years line up with the existence of Paradise Theatre. In an article published in 1984, Jackie Wilson said, “Detroit was the Paradise Theatre, the Flame Bar, and Al Green. Berry Gordy came later.” Gordy was incredibly influential in the music world, but it’s important to acknowledge who came first, just as it’s important to recognize Shoenberg, a well known but not very popular composer, for building the foundations of atonal classical music.

After I left the museum, I decided to walk a few blocks down Woodward Avenue to where Orchestra Hall still stands. I stood across the street and watched the clouds roll across the blue sky over the hall and imagined what it would have been like all those years ago, without the new Max M. and Marjorie S. Fisher Music Center attached to the side, with the big Paradise marquee suspended over the lobby doors. After spending hours upon hours of my own time in that building, it seemed unfathomable that I hadn’t heard of Paradise Theatre until so recently.

~

About seventy years ago, two Detroit neighborhoods, the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, were destroyed, ultimately to make way for a new freeway. It was part of a nationwide urban renewal program in the 40’s and 50’s which resulted in the termination of thriving black communities all over the United States. The idea was that cities would receive federal grants to be used to revive neighborhoods in bad shape, and to turn them into something more economically valuable. The demolition of the two neighborhoods was initially funded by President Truman’s Housing Act of 1949, which gave the jurisdiction needed to rid the city of old, run-down buildings, which, in this case, just happened to be the homes of thousands of low-income black Detroiters.

Since the 1930s, there had been an ever-increasing amount of pressure to build more highways. It was widely thought that freeways running in and out of cities would bring more people in to spend money on the local economy, and Detroit’s local economy was suffering exceptionally in the wake of the Great Depression. On top of that, starting during World War II, there was great migration of black southerners to northern states due to a promise of economic opportunity and better working conditions. Because of the amount of people moving at once, and segregation laws restricting them all to one area, however, many ended up poor, with crowded living conditions. When President Eisenhower passed the Federal-aid Highway act in 1956, Detroit was presented with the authority and funds to go through with the construction of Interstate-375, a mile and a half of road placed directly over the Black Bottom. This was the final nail in the coffin. By 1959, the neighborhood had been demolished and construction began.

In 2017, the Michigan Department of Transportation announced that I-375 would be replaced with a boulevard by 2024. The road has been in need of repair, and they decided that the cost isn’t worth the small number of benefits a renovation would provide. The boulevard will make the city more accessible and inviting, and it’ll provide more space for commercial buildings, or, perhaps, neighborhoods.

The Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods were the center of black culture in Detroit before their demolition. More than 300 black-owned businesses existed in Paradise Valley, and the Black Bottom was a rarity, a place where black families, though often overcrowded and living in run down houses, could truly feel at home amidst rampant racism. It was a substantial waste.

Although Paradise Theatre doesn’t exist under the same name anymore, the fact that the building still stands is representative of so many things. It survived the neighborhood after which it was named only because it stood in a predominantly white area, and it mattered to more people than just those who lived in the Black Bottom. Unfair is an understatement.

~

Orchestra Hall is more than a building, it’s a symbol of something that was almost erased, and thank goodness it wasn’t. An article published in the Detroit Free Press says, “The (Paradise Valley and Black Bottom) neighborhood(s) and (their) estimated 350 black-owned businesses are mostly a fading memory in aging residents’ minds,” and in a lot of ways, Orchestra Hall stands to serve as a reminder of an era of rich black culture in Detroit that should not be forgotten.

I can imagine too well what it must have been like to experience the Paradise Theatre, and I’m incredibly jealous of everyone who did. I sat in the third row from the front of the balcony one day, waiting for a concert of Debussy and Ravel to begin, and I could imagine the voice of Sarah Vaughn drifting to me as if through honey colored liquid. Everyone who attended a concert at the Paradise was part of something so big. The performers would connect with the audience in a way that is so rare in an auditorium of over 2,000. “When you walk in today, part of the magic is that you’re walking into history,” Mark Stryker said, “it looks the same, it sounds the same. You can feel the ghosts of all of the people who have been there.”

Comments